I recently presented a postmortem for the game I worked on for Global Game Jam 2024, Wally’s Wacky Walk. You can watch it here (along with other presentations from the IGDA Twin Cities community), and you can download the game here!

Posts Tagged with video games

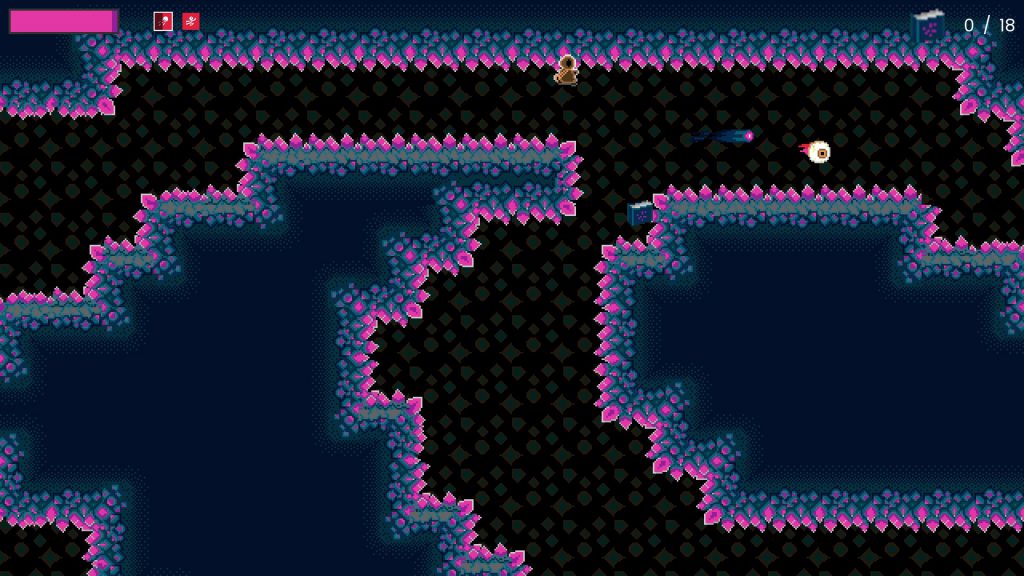

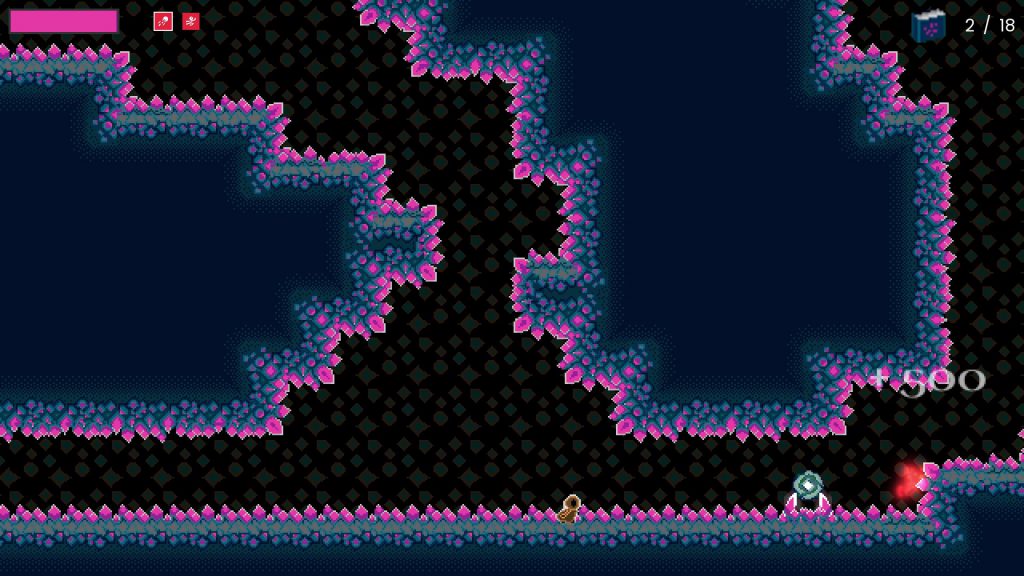

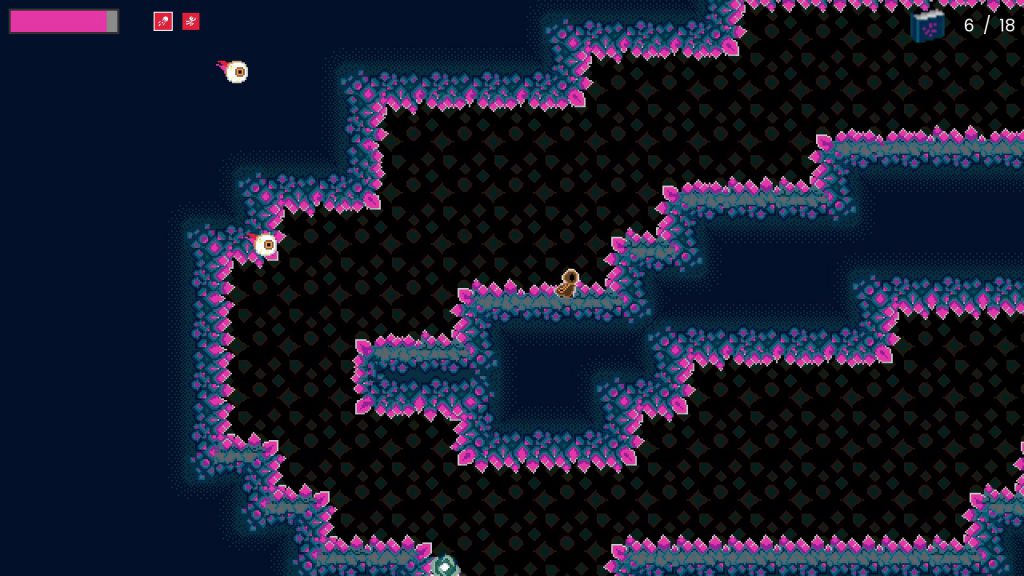

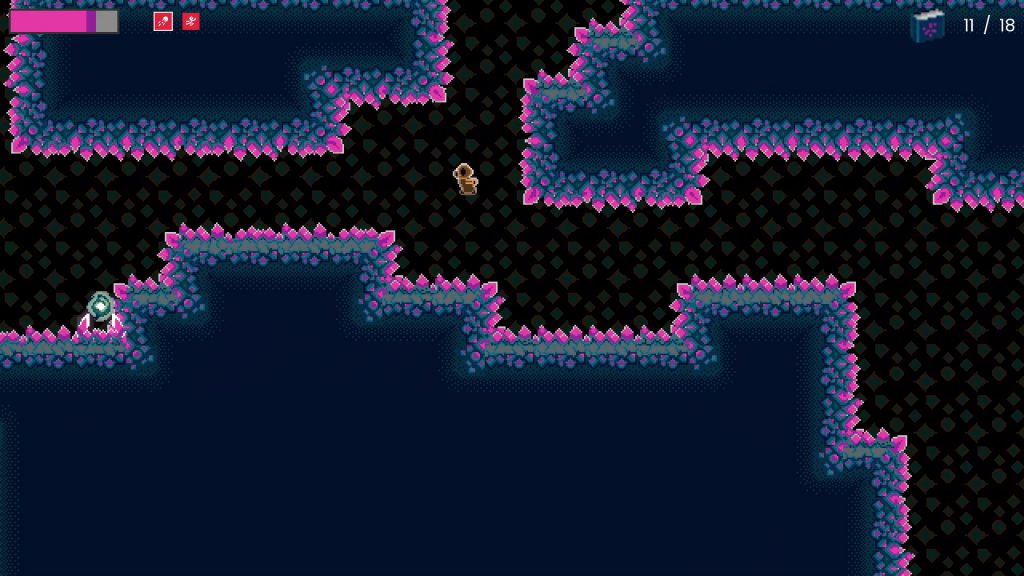

Postmortem: Black Hole Battle

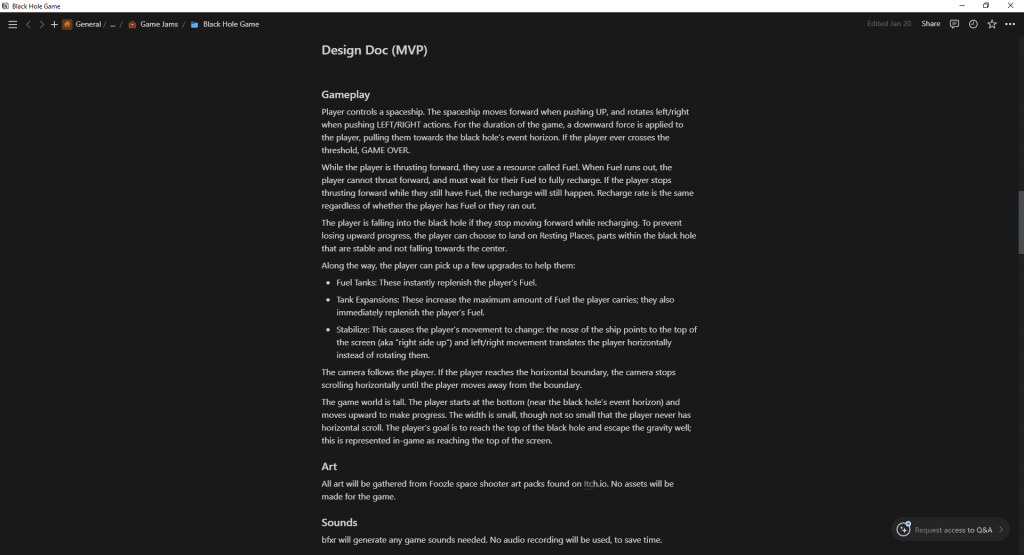

This year, I participated in Global Game Jam. In preparation for it, I decided to make a game in 16 hours, or one week’s worth of my game development time. What I wanted to focus on, in particular, was scoping the game accurately; in other words, I wanted the game’s scope to only encompass what I thought would be feasible within a week.

16 hours is the amount of time I’ve estimated spending doing game development during a typical week.

How did I do? Read on to find out!

Planning Phase

Day 1 (Saturday)

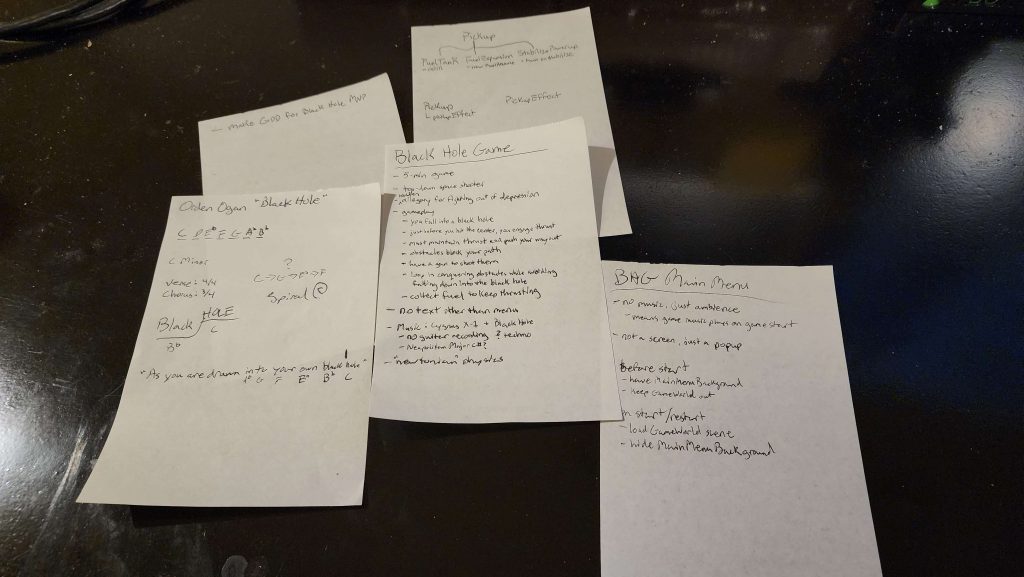

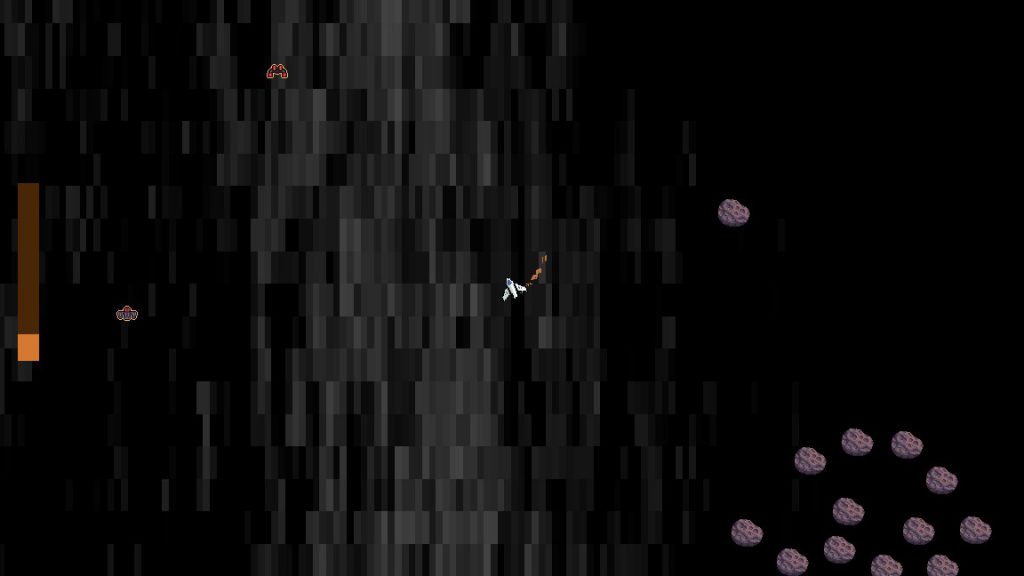

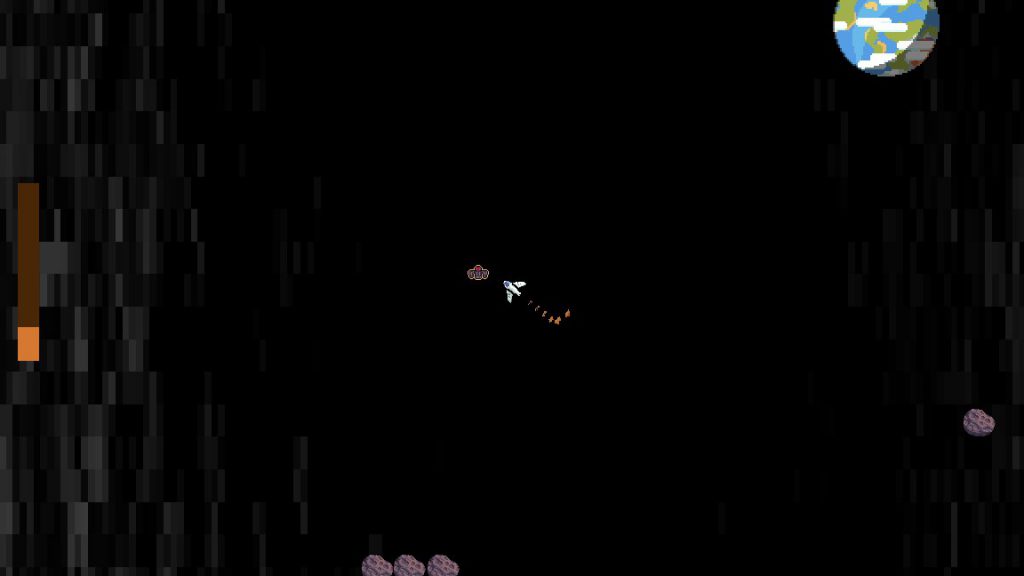

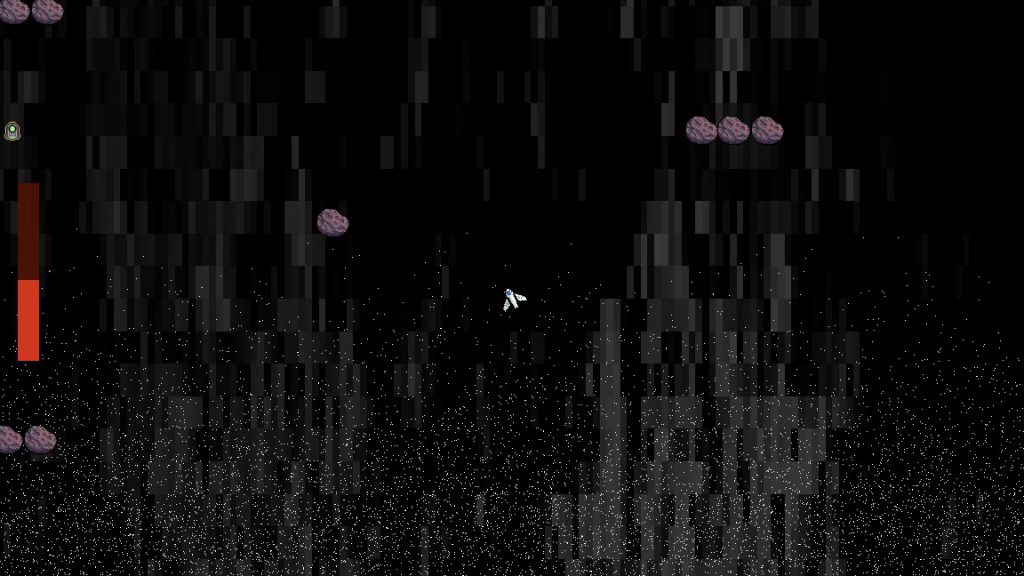

I spent a couple of hours on Saturday roughing out the game idea. I wanted to make a top-down space shooter, and I wanted the player to fight against a black hole’s pull and escape its gravity well. This theme was meant to be both literal and figurative, with game elements hinting an allegory of a fight against depression. To save myself the trouble of coming up with a good name right away, I used the working title Black Hole Game.

There would be two kinds of movement: rotational, where the player’s ship rotates and moves forward; and slide, which emulates classic top-down space shooter movement, such as Space Invaders or Galaga. There would also be shooting combat, with multiple guns for the player to collect, obstacles to shoot down, and enemies to dogfight and defeat.

A direct influence was a game called Laser Age, but I doubt that one is familiar to most people; I played it a lot when I was a kid.

This was a solo project, so I decided that there would be no custom art made for the game; everything had to be found in pre-existing art packs. I spent some time searching, and eventually purchased a few packs from an artist in a style that I liked (the Void packs from FoozleCC on Itch.io). For sound effects, I wouldn’t do any recording myself; either I’d find the effects online or I’d generate them with BFXR.

I chose to compose and mix the music. I had an idea of mashing the themes from two songs together: Rush’s Cygnus X-1 (Book 1: The Voyage) and Orden Ogan’s Black Hole. Both of these songs are themed around black holes, representing the dual literal/figurative theme I sought to represent. Although it would have been simpler to relegate this to external sourcing (as I did the art), I enjoy making music, so wanted to keep this part for myself.

I’d use Godot 4 to make the game. My long-term project, Dice Tower, is being built with Godot 3.5, so I wanted to get more experience using the latest version of Godot, particularly since that’s what I’d be using for Global Game Jam.

Finally, I set a deadline for the entire endeavour: Saturday, January 20th, 2023 at 5:00pm CST. In the spirit of a game jam, I wanted a clear, strict end time to force me to complete the project.

With my ideas set, I spent Sunday and Monday engaged in other activities. Come Tuesday, I was raring to go.

Day 2 (Tuesday)

My work period was in the evening. My only task this day was to create a game design document and a timeline for when I was going to work on certain tasks. I gave myself a one-hour time limit for doing all of it; the idea was that limiting how much time I had to plan would keep me from adding scope creep.

I used a modified version of the Pomodoro technique for consuming that hour of time. I’d do fifteen minutes of work, then take five minutes of break time. For the first block of work time, I spilled out as many ideas about Black Hole Game as I could. After the five-minute break, I spent the next fifteen minutes going through six randomly-drawn cards from my Deck of Lenses, writing down answers to how Black Hole Game might be seen through each lens. The final fifteen minute block was spent furiously typing out the actual game design document, or what was actually going to make it into the game. That brought me to 55 minutes of work; the final five minutes were spent taking my game design document and scheduling out which tasks would be worked on when.

I think timeboxing the game design period proved useful. Only a small amount of the many ideas I’d come up with made it into the design doc, and that was solely because I didn’t have enough time to write them all down. Since there were fewer things, it limited the scope of what Black Hole Game was going to be. All that remained was to see whether or not that small amount of scope was achievable.

Some of the ideas that were left on the planning room floor included the guns and shooting-oriented mechanics; the gameplay would solely focus on movement.

Development Phase

Day 3 (Wednesday)

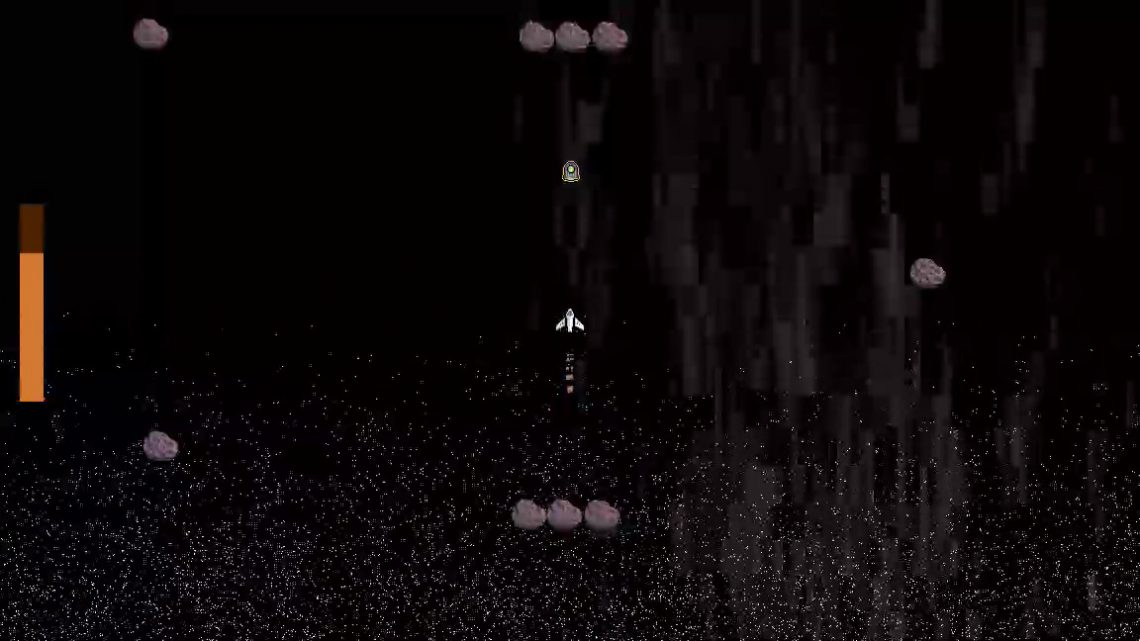

My time period was both morning and evening. Accordingly, I focused on roughing out the core of the game: movement mechanics and endgame triggers. My goal for the end of the day was to have a playable minimum viable product.

After creating the Godot project, I started implementing the player spaceship. I added the rotation-based movement first, spending a bit of time trudging through trigonometry (and the CharacterBody documentation) to figure out a simple implementation. Once this was mostly functioning as desired, I added the alternative sliding movement style, as well as the ability for the game to switch between the two movement styles seamlessly. Finally, I added constant downward velocity, simulating the pull of a black hole.

I added a debug key to let me freely toggle back and forth between the two styles of movement, even though my ultimate goal was to trigger this change through a pickup. I didn’t remember to take it out of the final build, so any player that figures out what the bind is can cheat the game. ;P

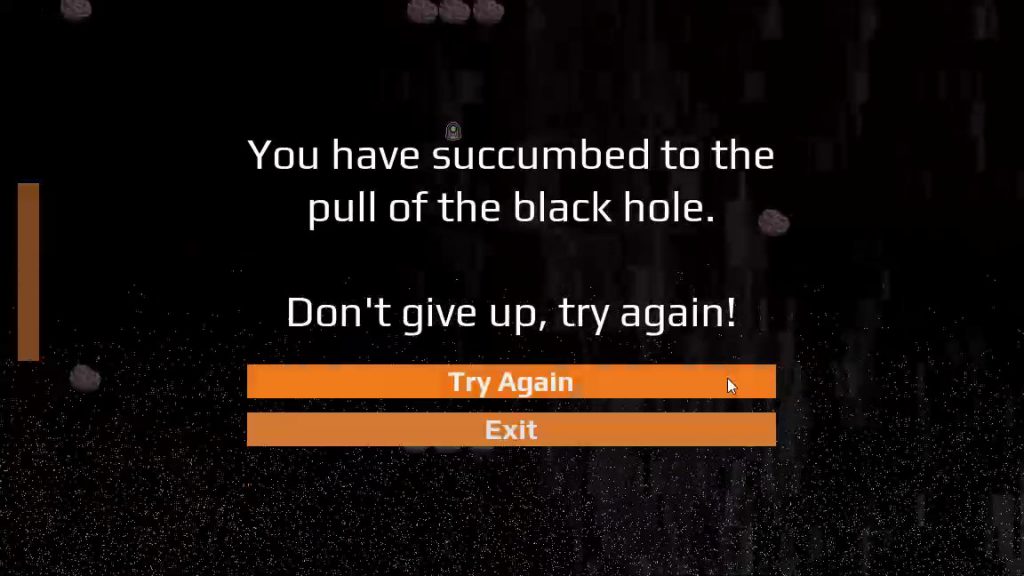

Once the player movement was working, I fleshed out my test game world into a fuller experience. I created some simple asteroid platforms for the player to rest their ship upon. I also made a couple of debug endgame zones: a red one for the black hole bottom, signifying defeat; and a green one to indicate where victory would be given to the player. In both cases, I showed a rudimentary test popup to communicate this endgame state. At this stage, the loss and victory zones were not too far away, for ease of testing.

With a game world in place, I worked on creating the Fuel mechanic. This limited how long the player was able to use their forward thrust, and with it the ability to drive against the black hole’s pull, and would create the game loop of moving from resting place to resting place without running out of fuel along the way. The implementation itself was simple: I made a custom resource that tracked how much fuel was in a given fuel tank, how long it took for the fuel to recharge, and signals to indicate when fuel was depleted or replenished. I then gated the player’s forward movement behind whether they had fuel in the fuel tank; if the player ran out of fuel, they couldn’t thrust forward until the tank recharged to full.

The last thing I tried was an experiment to render a black hole through Godot’s shader system. I tried a few shaders I found online, but none of them worked with initial implementation. Eventually, I decided that this wasn’t worth continued pursuit, and I axed it from my todo list.

By the end of the day, I had my MVP working: the player ship moved as designed, they had a fuel resource to manage, and places where they would trigger defeat or victory upon touching. I was feeling good about my chances meeting the planned scope.

Day 4 (Thursday)

Today, I only had a couple of hours in the morning to do game development work. Knowing this ahead of time, the only work I scheduled for that day was implementing a UI display for the fuel gauge and a Pickup system with three implementations: Fuel Tanks (instant refuel), Tank Expansions (refuel and expand the player’s tank capacity) and Stabilize (temporarily activate the Slide movement style). The day went as planned, and I implemented all of those thing by the end of my game development time. Once again, my confidence in the game scope increased.

Day 5 (Friday)

Once again, I only had a morning’s couple hours to work. Originally, my plan was to implement sound effects, but I changed my schedule to work on music, instead; I figured the timeboxing would be more useful for roughing out a composition than figuring out sound effects and how to implement them.

This time, I encountered difficulty. I had specific ideas for how I wanted to make the music, and I spent an hour messing around with various virtual instruments to try and get better sounds. Ultimately, most of that time was wasted, as I reverted to using the sounds I’d had in the first place.

Because of that wasted time, I rushed my way through a composition, and at the end of my gamedev work period I still didn’t have a fully composed piece of music, let alone the victory and defeat variants and the actual in-game implementation.

At this point, I became worried about whether I could still meet my planned scope. Were it not for my strict limit on when I would be allowed to work, I probably would have forced myself to finish the music on Friday night, against my work-life balance needs; instead, I forced myself to stick to the plan, and resolved to finish things as soon as I could on Saturday.

The Final Push

Day 6 (Saturday)

This was the final day for developing Black Hole Battle (the final title of Black Hole Game). I had ten hours, from 7am to 5pm, to finish development. By my self-imposed standards, this included publishing the game and making it available for people to play.

First, I had to catch myself up from where I’d gone off-plan. I spent about an hour finishing the music composition; ultimately, I was very pleased with it, and it decently accomplished my composition goal of merging Rush and Orden Ogan. I also threw together some short themes to play during defeat and victory.

With the music composed, I started work on implementing the music into the game. I thought I’d save some time by stealing some code from Dice Tower’s sound management system and converting it to work in Godot 4; the reality was that this system was built on top of a number of internal systems which I also had to port over to make the entire system work. Altogether, that was another two hours spent. Once the foundational systems were in place, it didn’t take too long to wire up the logic for when each piece of music should play.

Next, I jumped into creating and integrating sound effects. With time being compressed, I opted for using BFXR to create almost all of the needed sound effects (the lone exception being an ambient background noise, which I wound up stealing from Dice Tower). I worked my way down the list of planned effects, crossing out any which I felt I could do without. By early afternoon, all the necessary sound effects were created and implemented.

At this point, I needed to add the bare minimum requirements for UI, menus and game restart logic. I spent 20 minutes finding and adding two fonts: one for stylistic display, like headings, and one for button and paragraph text. Next, I created a Theme resource and added just enough customization to reduce the cost of duplication (like consistently styled buttons). With that theme, I created and styled my main menu, pause menu, and endgame menu popups. Once the menus were made, I added logic for when they would appear. Finally, I created proper game start and restart logic and integrated that with my menus. Once these things were finished, I had a fully functional and minimally polished game. To confirm I had a functional build, I did a test export of the game and proved that it still worked.

Fortunately, I only had one screen resolution to worry about; my experience supporting multiple resolutions in Dice Tower cautioned me against making the effort to do more than that.

By this time, I had about an hour left to add whatever content and polish I could muster. I threw together some simple game objects (based around the asteroids and planet from the purchased art packs) and tossed them into an expanded game world, along with generous placement of player pickups. I also adjusted the player movement mechanics slightly, to make them feel more responsive. Finally, I hid the debug graphics for the endgame zones, and, for the black hole bottom, I added a particle effect to indicate some kind of churn and swirl; hardly a realistic representation of what a black hole would actually look like, but it felt cool and only took a minute to spin up.

With minutes to spare, I created the final export and uploaded Black Hole Battle to a hosting service. The project was finished, and precisely at 5pm! I shared the project with a few friends, then went upstairs to have supper with my family.

Takeaways

The primary goal for Black Hole Battle was to practice scoping for a specific amount of time. Given this, I was successful: I accomplished all of the features I’d set out in the game design document.

Did I complete every single task? No, but that was never the goal; it’s impossible to complete a project exactly as drawn up, and there must be room alotted for adjustments. What I was expecting of myself was to implement all the planned game features and to release them in a polished state; in this effort, I succeeded.

Was the game itself perfect? No; the audio balance between SFX and Music was off, I didn’t really nail the planned thematic duality of black holes and crippling depression, and the small amount of gameplay means it doesn’t take long to fully explore what the game offers. My focus wasn’t on making Black Hole Game the best game it could be, but on making it good enough to be releasable. The game isn’t perfect, but it’s “good enough” to feel like a complete game.

At no point did I force myself to work longer than the hours I’d planned. I resisted the urge to crunch when I felt like I was falling behind, and I still found a way to deliver a completed project. This was a rare success, as previous projects have either ran horrifically over scope or had significant cuts to features and quality to release them on time. Hopefully, I can use this as a standard to plan other projects by.

Conclusion

I wanted to prepare for Global Game Jam by making a one-week, precisely-scoped project. With Black Hole Battle, I successfully achieved this goal, and it left me feeling confident going into Global Game Jam.

How did the jam itself turn out? You’ll find out soon, when the IGDA Twin Cities Global Game Jam postmortem meeting is uploaded to YouTube! That said, I consider the work I did on Black Hole Battle an important factor in how my time at Global Game Jam went.

Here is the final result for Black Hole Battle, for those who wish to try it out. I have no plans to make further changes for it, but feel free to leave feedback so I can apply it to future projects.

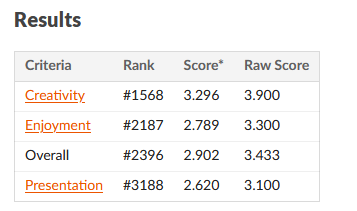

Postmortem: Dice Tower

This July, Rebecca and I took part in Game Maker’s Toolkit Game Jam 2022 (an annual game jam hosted by the creator of YouTube channel Game Maker’s Toolkit, Mark Brown), making a game called Dice Tower in only fifty hours. It was our first game jam in a long time, having spent the last three years focusing (and failing) on making our “first big release”. Those fifty hours proved to be an intense, fulfilling experience, and I want to examine how things went. I’ll start with the goals that Rebecca and I made, continue into what happened during the jam, and conclude with whether I felt our goals were met and what we’ll do in the future.

Our Goals

First and foremost, Rebecca and I wanted to actually release the game! Our last jam effort, Rabbit Trails, never saw the light of day because we didn’t get the build submitted in time, and we were determined to avoid making that mistake again.

I wrote briefly about this experience as part of my retrospective on 2019.

To that end, we explicitly wanted to scope our game small enough that it had a realistic chance of being completed by jam’s end. Further supporting that goal, we also decided that we would avoid trying to come up with something “clever”; we would be fine with coming up with feasible and fun ideas, even if they might be ideas that other people were likely to come up with. Finally, we determined that we would specifically make a 2D side-scrolling platformer, because that was the genre we were most familiar with; we didn’t want to waste time figuring out how to do a genre that we lacked experience in making.

Based on what had happened in previous jams, we had a few other goals we wanted to meet. Given that our previous games felt bland, we wanted to make sure whatever we made felt more polished and juicy, thereby increasing how good it felt to play. Previous jams had left us feeling burnt out and exhausted, and, while that is a traditional hallmark of game jams, we strongly wanted to avoid feeling that way at this jam’s end, so we made plans to limit how many hours we’d work per day so that we’d have time to relax and get our normal amount of sleep.

Separate from the in-jam goals, we had one ulterior objective: we wanted to see if the idea we came up with was good enough to develop further into a small release. The game we’d been working on, code-named “Squirrel Project”, was still very much in the early prototyping stage; we’d built and tried a lot of things, but made little progress in actually putting together a full game experience. Both of us felt concerned with how much time we were taking in making a “small game”, so we were interested in seeing if doing game jams might give us smaller concepts that would be easier to develop and release quickly. This jam would serve as a proof of concept for this theory.

Day One (Friday, 7/15/22)

The day of the jam arrived. Our son was off spending the weekend with relatives, we’d prepared our meal plan for the next couple of days, and I’d taken time off from my day job. We sat around my laptop, awaiting Mark Brown’s announcement of the theme. At noon, the video was released, and we saw the theme emblazoned on the screen:

Initial Planning

I hated the theme at first impression. One of my takeaways from working on Sanity Wars Reimagined (our first-ever full release) was that working with randomness in game design was hard, and now we had a game theme which strongly implied designing a game focusing around randomness. In my mind, it would be harder to design a game around dice that wasn’t random in some way. Concerned now with whether we would have enough time to make a good game, I started brainstorming ideas with Rebecca.

We spent that first hour working out an idea; the first idea we hit upon wound up dominating the rest of our brainstorming session, to the point that we didn’t seriously entertain anything else. The game would be a rogue-lite platformer, where you moved to various stations and rolled dice to determine which ability you got to use for the next section of gameplay. Throughout the level would be enemies that you could defeat to collect more dice, which would then give you a better chance to roll higher at the ability checkpoints, thereby increasing your odds of getting the “good” abilities.

I intentionally wanted to minimize the randomness of our game so that players felt they had some level of control over the outcomes of dice rolls, and I liked the idea of using dice quantity to achieve this outcome. The more dice you add to a roll, the more likely you are to get certain number totals. This is known as a probability distribution.

At the end of that hour, we formally determined that this was the idea we wanted to work with. Rebecca started crunching out pixel art, and I got to work making a prototype for our envisioned mechanics.

That Old, Familiar Foe

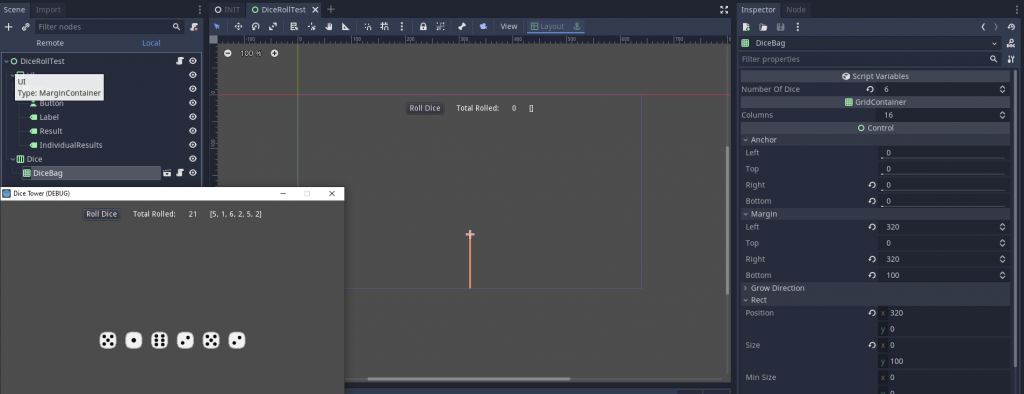

The next few hours of my life were spent working on the various elements that would serve as a foundation for our mechanics. I threw together some simple dice code, along with dice containers that could roll all the dice they were given. I also pilfered my player character and enemy AI code from Squirrel Project, to jumpstart development in those areas.

But something happened as I started trying to work out how I was going to make the player’s abilities work: my brain began to freeze up. This was a frighteningly familiar sensation: I’d felt this way near the end of developing the original Sanity Wars (for Ludum Dare 43). Dark thoughts started clouding my mind:

There’s not enough time to make this game.

You’re going to fail to finish it, just like your last game jam.

Is what you’re feeling proof that you’re not really good enough to be a game developer?

Slowly, I forced myself to work through this debilitating state of mind. After several more hours, I came up with a janky prototype for firing projectiles, and a broken prototype for imparting status effects on the player (like a shield). It occurred to me that if I was having this much trouble making something as simple (cough cough) as player abilities, then how was I going to have time to fix my glitchy enemy AI, and develop the core mechanic of rolling dice to gain one of multiple abilities, and make enough content to make this game feel adequate, let alone good. Oh, and then there was still bugfixing, sound and music creation, playtesting…

It finally hit me: This idea wasn’t going to work. There was simply too much complexity that was not yet done, and I was struggling with the foundational aspects that needed to be built just to try out our idea. There was no way I would be able to finish this vision of our game on time.

My mind in shambles and my body exhausted, I shared my feelings and concerns with Rebecca, and she agreed that we needed to pivot to a new idea. We tried to come up with something, but we were both too tired to think clearly. Therefore, we decided to be done for the evening, get some supper, and head to bed.

Note the lack of planned relaxation time.

As I lay in bed, I fretted about whether we could actually come up with a new idea. That first idea was by far the best of what few ideas we’d been able to come up with during our brainstorming session; how were we going to suddenly come up with an idea that was good enough and simpler? With these worries exhausting my mind, I fell asleep.

Day Two (Saturday, 7/16/22)

The next morning, at 6am, I woke up, took a shower, and played a video game briefly. This was my normal morning routine during the workday, and I was determined to keep to it. At 7am, I grabbed a cup of coffee and sprawled out on the couch, pad of paper and pen resting upon an adjacent TV tray, prepared to try and come up with a new idea.

Rebecca joined me at 7:30am, after she did her own waking routines.

The New Idea

I wrote down the elements we already had: Rebecca’s character art and tileset from her previous day’s work, some dice and dice containers, and a player entity that was decently functional as a platformer character. If our new idea could incorporate those elements, then at least not all of yesterday’s work would go to waste.

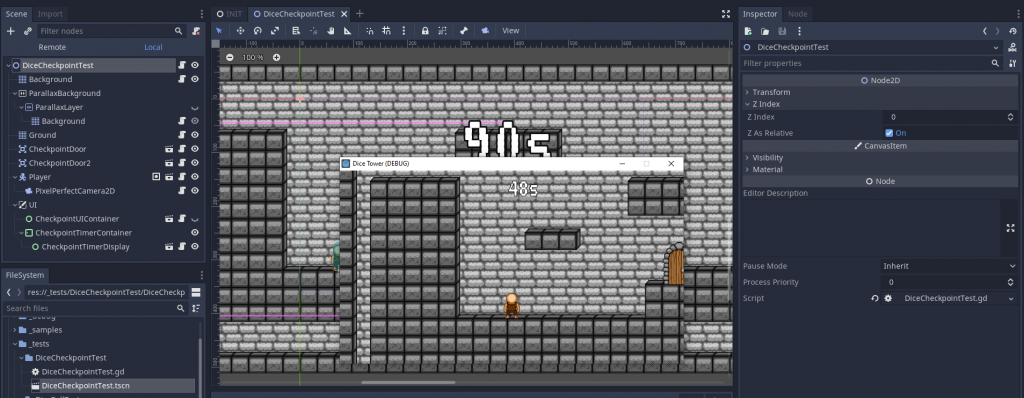

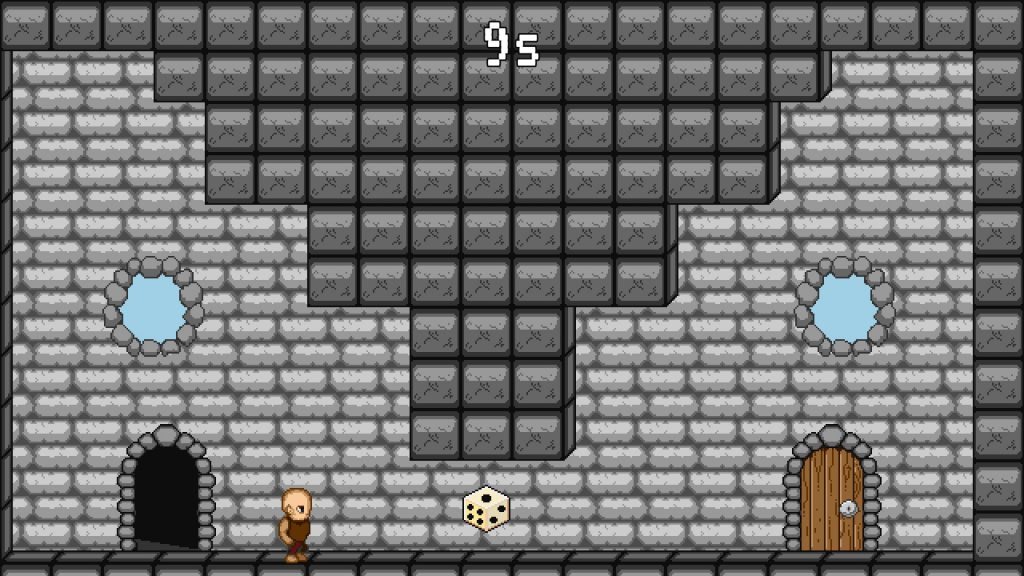

After thinking about it for a long while, I hit upon an idea: what if you rolled dice to determine how much time you had to complete a level? As you moved through each level, you could collect dice and spend them at the end-of-level checkpoints to increase your odds of getting more time to complete the next level. If that were combined with a scoring system involving finding treasure collectibles that were also scattered throughout each level, then there’d be potentially interesting gameplay around gambling how many dice you’d need to collect to guarantee that you had enough time in each level to collect enough treasure to get a high score.

I pitched the idea to Rebecca, and after some discussion about that and a few other ideas, we decided this was the simplest idea, and therefore had the best chance of being completed before the deadline. Fortunately, this idea also did successfully incorporate most of the elements that we’d worked on yesterday, so we didn’t have to waste time recreating assets. On the other hand, this idea needed to work; there was likely not going to be any time to come up with another plan if we spent time on this one and it failed.

Our idea and stakes in mind, Rebecca and I once more commenced our work.

Slogging Through the Day

I created various test scenes in Godot. Slowly, I began to amass the individual systems and entities that I’d eventually put together to form the gameplay. Throughout the day, I felt very sluggish and lethargic mentally; this was likely a side effect of the burnout I’d put myself through yesterday. I kept reminding myself that some amount of progress was better than none at all, but it still didn’t feel great.

By the start of that evening, I had a bunch of systems, but nothing that fully integrated them. Taking a break, I went outside for a walk and some breaths of fresh air. As I trod the trails in our neighborhood, I worked out the game’s next steps. I reasoned that if I continued to put each system and entity together in isolation and test them, I stood a realistic chance of running out of time to put everything together into a cohesive game. Therefore, I decided to forgo this approach, and simply put everything together now, and build the remaining systems as I went along. This flew in the face of how I traditionally prefer to program things, but I resolved to set aside my clean code concerns and focus simply on getting the game working.

The Late Evening Dash

Not long after I returned from my walk, it became 7pm. This was the twelve-hour mark, and in our pre-jam plans I’d determined that I wouldn’t work more than twelve hours on Saturday. Yet I still didn’t have much that was actually put together. I was now faced with a conundrum: should I commit to stopping work now, and risk not having enough time tomorrow to finish the minimum viable product?

Ultimately, I decided that I would try to get an MVP done tonight, or at least keep working until I felt ready to stop. Three hours later, while that MVP was still incomplete, I had put together the vast majority of what was needed to make the game playable: a level loading system, the dice-rolling checkpoints, dice collection (though said dice weren’t yet connected to the checkpoints), the level timer and having it set from rolling the checkpoint dice, rudimentary menu UI, and player death. At this point, I felt that continuing to work would just cut into my sleeping time, and I was still determined to get a proper amount of sleep. At the least, those few hours had produced enough progress that I felt confident that I could finish things up tomorrow morning.

I quickly prepared for bed, and after watching some YouTube to wind down I fell asleep.

Day Three (Sunday, 7/17/22)

That morning, I woke up at 6am, as usual, but this time I skipped all of my morning routine save the shower. By 6:30am, I was at my computer and raring to go.

Blazing Speed and Fury

The first thing I did was export the game as it currently was. I’d been burned enough times by last-minute exports that I was determined to make sure that didn’t bite me in the butt this time. Fortunately, this time there were no export-specific crashes or bugs, so I resumed work on the game proper.

For the next several hours, my mind singularly focused on getting this game done. I finally made the checkpoints accept the dice you collected, thus completing the core loop of rolling dice to determine the time you had to make it through the level. I added game restart logic, added transition logic for when the player was moving between levels, added endgame conditions and win/loss logic, and fix various bugs encountered along the way. I also realized that I wouldn’t have time to implement a scoring system, so I unceremoniously cut it from the MVP features.

Around noon, I finally had the game fully working. I could boot the application, start a new game from the main menu, play through all the designated levels, and successfully reach the victory level to win the game (or run out of time and lose). If nothing else, we at least had a playable game!

Final Push

The game jam started at noon on Friday, and as it was now noon on Sunday that meant 48 hours had passed. Thankfully, the jam had a two-hour grace period for uploading and submitting games to Itch.io. That meant I had less than two hours to jam as much content and polish into the game as I could before release!

I blazed my way through creating six levels, spending less than an hour to do so. Of course, that meant I had little time to balance the levels properly, beyond ensuring they could be completed in an average amount of time. One thing I did spend time on was adding the various pieces of decorative art Rebecca made to each level. It might seem frivolous to add decorations, but I think having a nicely-decorated level goes a long way towards breaking up level monotony and sameness, and honestly it didn’t take that long for me to add those things.

After a few trials, I hit upon a solution for balancing the randomness for the dice checkpoints: I’d give the player six free seconds at the start of each level, and a single die at each checkpoint (in addition to the ones collected through gameplay). As I playtested the level, that at least felt long enough that, using probability curves, the average player could have a decent chance of finishing each level.

Intentionally, I chose to not focus at all on adding sound effects and music. My reasoning went thusly: players would probably prefer to have more content to play through than have sound and music with very little content. It made me remorseful, because sound can make an okay game feel great, but there just wasn’t enough time to do a good job of it, so I decided it was better to just cut audio entirely.

Finally, at 1:30pm, I looked at what we had and determined it was good enough. Rebecca had been working on setting up our Itch.io page, and I gave her the final game build export to upload to the store page. We submitted the game just in the nick of time; shortly after our submission was processed, Itch.io crashed under the weight of thousands of last-minute uploads. While this server strain prevented us from adding images for our game page (we got them in later), at least we already had the game uploaded and submitted, so we weren’t in danger of missing the deadline.

Rebecca and I looked at each other. We’d done it! We’d successfully made a game and submitted it! We spent the rest of the afternoon out and about on a date, taking advantage of our last bits of free time before returning to parenthood the next day.

Feedback

Over the next week, our game was played and rated by people. We received multiple comments about how people enjoyed the core idea, which was encouraging.

A couple of our friends from the IGDA Twin Cities community took it upon themselves to speedrun our game. This surprised me, because I thought the inherently random nature of our game would be a discouragement from speedrunning. They told me they enjoyed it a lot, however, and over the course of that week they posted videos of ridiculously speedy runs and provided good feedback.

By happenstance, the Twin Cities Playtest session for July was that same week, so Rebecca and I submitted Dice Tower to be played as part of that stream. Mark LaCroix, Lane Davis, and Patrick Yang all enjoyed the game’s core concept, and gave us tremendous feedback on where they felt improvements could be made, as well as different directions we could go to further expand and elaborate on the core mechanic. It was a great session, and we are greatly indebted to them for their awesome feedback.

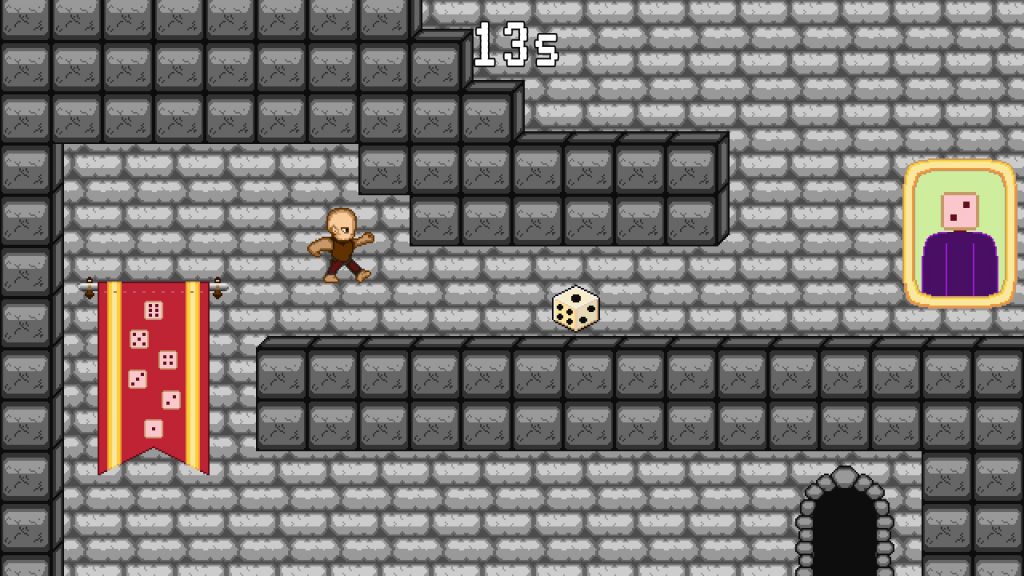

After the play-and-review week had passed, Mark Brown made his video announcing the winners of the jam, and we got to see our final results online (we did not make it into the video, which only featured the top one-hundred games).

For a game jam with over six thousand entries, we did surprisingly well, placing in the top 50% in overall score. Our creativity score was in the top third, which pleased me greatly; it felt like further validation that our core concept was good enough to build on.

Reflection

I want to circle back to those goals Rebecca and I set before the jam, and see how we did in meeting them. There were a couple of other takeaways I had as well, which I’ll present after looking at the goals.

Did We Meet Our Goals?

First and foremost, we wanted to release a game, and we did! That was huge for us, given our last effort died in development. In particular, to release this game after the mental fracturing I endured on Friday night, and having to pivot to a new idea, shows that, perhaps, we’re decent game developers, after all.

Did we scope our game properly? At the beginning, no, definitely not. Fortunately, we recognized this (albeit after spending a day on it), and decided to change to a more feasible idea. Even though we had to cut scope from the new idea as well, the core was small enough that we were able to make it in the time allotted. It gives us a new baseline for how much work we can fit in a given amount of time, which should serve us well in future endeavors.

It’s a similar story for our theme interpretation. Our first idea seemed simple, but turned out to be complex under the hood, as it’s a lot of work to not only add lots of different player abilities, but game entities (such as enemies) to use those abilities on. In hindsight, I laugh at how we thought that kind of game was feasible in 48 hours, with not nearly enough foundation in place beforehand. That said, once again, we pivoted from the complex to the simple, and the new theme interpretation was simple enough to be doable.

Ironically, I thought this would be a common enough idea that plenty of other people would do it, but I actually never encountered a mechanic similar to this during my plays of other jam games, and multiple people commented on the novelty of the idea. Perhaps our focus on coming up with a good idea instead of a unique one managed to get us the best of both worlds!

We stuck to our guns and made a 2D side-scrolling platformer, even though at times I felt like that made it more difficult to find a good theme interpretation. Because we knew how to work in that genre, it made our mid-development pivot possible; I don’t think we could have been successful in doing that if we’d tried to make something unfamiliar to us. Additionally, I think using a genre where dice are less commonly used led to coming up with something more unique than we might’ve if we’d done an RPG or top-down game (two genres I thought would be easier fits for the theme).

One area we did miss on was making this a polished release. The missing audio was sorely felt. That said, I really like the art that Rebecca came up with, especially the decorations, and I don’t regret the decision to cut sound in favor of making levels and placing her doodads. Honestly, despite the missing audio, the fact that this game was fun and playable made this jam release feel more polished than our previous jam efforts.

A big success we had was in self-care management. Even though we didn’t stick to the maximum hours per day we set before the jam, we took care to make sure we got enough sleep each night. The end result is that this is the first jam we’ve done that both of us didn’t feel utterly spent at the end of it. That allowed us to enjoy a lovely afternoon and evening together as a couple, and we didn’t feel totally shot for days thereafter. I think that also helped us have the energy needed to push us through to the finish line.

One final goal remains to be evaluated: was our game good enough to base a future release upon? The answer is “yes”. Based on the enthusiastic feedback we received, plus our own thoughts about where the concept could go, we’ve decided to put Squirrel Project aside and focus on making a full, but small, release out of Dice Tower. With some more features and polish, and maybe a dollop of background story to tie things together, we think Dice Tower could make a good starting point for our first paid release.

Additionally, we plan to take part in future game jams, and further explore the concept of making quick games to find small ideas with good potential.

Other Takeaways

There were some additional things we learned from the jam. These emerged as byproducts of the things we tried during the jam.

Our initial thoughts were that we’d spend our brainstorming session coming up with multiple ideas, and then make small prototypes for each of them and decide which of them was the one we wanted to make. It didn’t turn out that way; both our first and second attempts settled early on a single idea, to the point where we didn’t really have many other ideas that we seriously considered. I think that perhaps that’s just how Rebecca and I work; it’s easier for us to jump into an idea and try it rather than piece a bunch of ideas together and flesh all of them out on paper. Perhaps in our next jam, then, we’ll deliberately settle on an idea right away and just go for it, making explicit allowance for pivoting if it starts feeling like too big an idea to work with.

Personally, I also learned that I need to let go of trying to test every little thing in isolation. That may be a good approach for building long-lived, stable systems, but for something as volatile as game prototyping it just slows the process down too much, with no game to show for it. By putting things together as early as possible, it makes things feel more real because it is the real game! I’ll keep this in mind for future projects, to just make a go of it right off the bat, and save my efforts to make things nice and tidy for when the ideas are codified and made official.

Conclusion

Ultimately, I’m glad Rebecca and I decided to participate in GMTK Game Jam 2022. It feels exhilarating to not only finish a game in that short amount of time, but to defeat some of my internal demons from previous jams in the process. We feel more confident in our ability to develop and release games, and we’re excited to tackle making the full release of Dice Tower.

It’ll be interesting to compare this postmortem with the postmortem for whatever that game becomes!

In the meantime, though, feel free to try out our jam release of Dice Tower and let us know what you think!

Postmortem: Sanity Wars Reimagined

After seven months of development, Rebecca (PixelLunatic) and I have released Sanity Wars Reimagined! Along the way, we learned a lot, lessons we hope to apply to future games we develop. In this article, I want to dig a little bit into what we learned, from what we were initially trying to do to where we wound up, and the various lessons learned and mistakes made along the way.

You can check out Sanity Wars Reimagined on Itch.io!

This project started with a discussion Rebecca and I had about where things were from a long-term standpoint. For the past few years, we’d attempted, and abandoned, various prototypes, and it seemed like we were still far off from actually releasing a product. At the time, I had just come off of a month-long project exploring the creation of game AI; my intent was to start another project aimed at making improvements to the dialogue system. During our discussion, however, Rebecca pointed out that, while our ultimate goal was to make games and sell them, we had a bad habit of not committing to anything long enough to get it released. What’s more, she was concerned that this pattern of starting and abandoning projects wasn’t good for our morale.

She was right to be concerned about this; I’d felt that making an actual release was still a point far off in the distance, and this was making it easier for me to accept the idea of working on non-release projects, to “gain experience”. How would we ever learn how to improve, though, if we never got our projects to a releasable, playable state? Only two of our game jam games and one of our prototypes had ever been given to other people to play, so we had very little feedback on where we needed to improve. I realized that we couldn’t keep waiting to release something until “we got better”; we needed to make something and release it, however bad it may be.

We decided that we would start with a small project, so that it would take less time to get it to a releasable state. To that end, we determined that the project should be a remake of our first jam game, Sanity Wars. By remaking a game that was already released, we thought, we could focus on actually building the parts needed to make the game work; since I’d made those things work previously, we would hopefully avoid the pitfall of trying to create mechanics that were beyond our current skill to implement, or would take too much time to build. Why Sanity Wars? Out of all the previous jam games we’d made, it seemed like the most successful one, so we thought we could just add some polish, redo the art (since Rebecca did not do the original’s art), and it would be fine.

With that, our next project was set: Sanity Wars Reimagined. We would stay faithful to the mechanics of the original, aiming only to remake them in Godot, as this would be quicker than trying to iterate and make new mechanics. I would also take the opportunity to try and make systems that would be reusable in future games; ideally, we would treat Sanity Wars Reimagined as a foundation that we would directly expand upon for the next game. Since the original Sanity Wars was done in three full days, I thought this project wouldn’t take long to complete. Accounting for our busy adult schedules, I estimated the work would take two weeks to complete; at most, a month.

It didn’t take two weeks. It didn’t take a month. It took seven months before we finally released Sanity Wars Reimagined on Itch.io. Along the way, we made significant modifications to the core mechanics, removing multiple parts that were considered essential to the original Sanity Wars; even with those changes, the end result was still not that fun (in our minds). There were many times during the development period where it felt like it was going to drag on and on, with no end in sight. All that said, I still think Sanity Wars Reimagined was a successful release.

Why do I think that? To answer that question, I want to examine what technologies we developed during the project, what mistakes we made, and what we plan to do to improve things for our next project.

Technologies Developed

A lot of what I made from a code standpoint was able to be imported back into my boilerplate Godot project, which will then be available from the start when I clone the Genesis boilerplate to make any future game project. In doing so, I’ve hopefully decreased the amount of development time needed for those projects.

Genesis is name of a tool I created in NodeJS that lets me keep a centralized Godot boilerplate template and create new projects from that boilerplate using simple commands in a command line interface. To give a non-technical summary, it allows me to quickly create and update new Godot projects that include common code that I want to reuse from project to project.

Here are some of the things that I’ll be able to make use of as a result of the work done for Sanity Wars Reimagined:

Resolution Management

There is a lot to consider when supporting multiple resolutions for a game, especially one that uses a pixel art aesthetic. I was already aware of this before committing to figuring out a solution for Sanity Wars Reimagined, but I underestimated just how much more there was to learn. The good news is that I created a solution that not only works for Sanity Wars Reimagined, but is generalized enough that I can use it as the starting point for future games.

I’ll talk in brief about some of the struggles I had to contend with and what I did to solve them.

For starters, when working with pixel art, scaling is a non-trivial issue. Because you are literally placing pixels in precise positions to render your art aesthetic, your scaling must always keep the same aspect ratio as your initial render; on top of that, it must specifically be increased in whole integer factors. This means you can only support a limited number of window sizes without messing up the pixel art. That plays a huge factor in determining what your base size is going to be; since most monitors use a 1920px by 1080px resolution size, your base needs to be a whole integer scale of 1920×1080, or else the game view is not going to actually fill the whole screen when it is maximized to fill the screen (aka fullscreen).

The way fullscreen modes are typically handled for pixel art games, when they attempt to handle it at all, is to set the game view to one of those specific ratios, and letterbox the surrounding area that doesn’t fit cleanly into that ratio. That is the approach I chose for my fullscreen management as well.

Godot does give you the means to scale your game window such that it renders the pixel art cleanly, and you can also write logic to limit supported resolution sizes to only those that scale in whole integers from the base resolution. However, there is a catch with the native way Godot handles this: any UI text that isn’t pixel-perfect becomes blurry, which isn’t a great look to have. I could have switched to only using pixel-perfect fonts, but that wasn’t the look I wanted the game UI to have. After spending a lot of time experimenting with ways to handle this in Godot’s settings, I determined that I would have to create a custom solution to achieve the effect that I wanted.

I wound up talking to Noel Berry (of Extremely OK Games) about how Celeste handled this problem, as its crisp UI over gameplay pixel art was similar to what I was hoping to achieve. He told me that they actually made the UI render at 1920×1080 at default, and then scaled the UI up or down depending on what the game’s current resolution was. This inspired me to create a version of that solution for Sanity Wars Reimagined. I created a UI scaling node that accepts a base resolution, and then changes its scale (and subsequently the scale of its child and grandchild nodes) in response to what the game’s current resolution is. It took a lot of effort, but in the end I was able to get this working correctly, with some minor caveats*.

* I’ll be coming back to these caveats later on in the article, when I discuss mistakes that were made.

Overall, I’m very pleased with the solution I developed for resolution management in Sanity Wars Reimagined, and ideally this is something that should just work for future pixel art-based games.

Screen Management

Another system I developed for Sanity Wars Reimagined is a screen management system that supports using shaders for screen transitions. Although my boilerplate code already included a basic screen manager that was responsible for changing what screens were being currently portrayed (MainMenuScreen, GameScreen, etc.), a significant flaw it had was that it didn’t provide support for doing screen transitions. This was going to be a problem for Sanity Wars Reimagined, as the original game had fade transitions between the different screen elements. I thus set out to refactor my screen management to support doing transitions.

In the original Sanity Wars, the way I accomplished the fade was through manipulating the drawn image in the browser’s canvas element (as the original game was built using HTML/JavaScript, the technologies I was most familiar with at the time). It was hardcoded to the custom engine I’d built, however, and there wasn’t a direct way to achieve the same effect in Godot. It’s possible I could have made the fade transition, specifically, work by manipulating the screen node’s modulation (visibility), but I didn’t feel comfortable making direct changes to node properties for the sake of screen effects, especially if I wanted to have the ability to do other kinds of transitions in the future, such as screen slides or flips; anything more complex than that would be outright impossible through mere node property manipulation.

My focus turned towards experimenting with a different approach, one based on using Godot’s Viewport node to get the actual render textures, and then manipulating the raw pixels by applying shaders to the render images of the outgoing screen and the incoming screen. Viewports were something I hadn’t had much experience with, however, so I wasn’t certain if the idea I had would actually work. To prove the concept, I spent a weekend creating a prototype specifically to test manipulating viewport and their render textures. The approach did, in fact, work as I envisioned (after a lot of research, trial, and error), so I proceeded to refactor the screen management system in Sanity Wars Reimagined to use this new approach.

When referring to screens here, I’m not talking about physical monitor screens; it’s a term I use to refer to a whole collection of elements comprising a section of the game experience. For instance, the Main Menu Screen is what you see on booting up the game, and Game Screen is where the gameplay takes place.

Overall, the refactor was an immense success. The fade effect worked precisely the way it did for the original Sanity Wars, and the system is flexible enough that I feel it should be easy enough to design new screen transition effects (in fact, I did create one as part of making the LoadingScreen, transitioning to an in-between screen that handled providing feedback to the user while the incoming GameScreen prepared the gameplay). Should I want to create different visual effects for future transitions, it should be as simple as writing a shader to handle it. (Not that shaders are simple, but it is far easier to do complex visual effects with shaders than with node property manipulation!)

Automated Export Script

After realizing that I needed to export game builds frequently (more on that later), I quickly found that it was tedious to have to work through Godot’s export interface every time I wanted to make a build. On top of that, Godot doesn’t have native build versioning (at least, not that I’ve found), so I have to manually name each exported build, and keep track of what the version number is. Needless to say, I wondered if there was a way I could automate this process, possibly through augmenting the Genesis scripting tools to include a simple command to export a project.

I took a few days to work through this, and in the end I managed to create functionality in my Genesis scripting tool that did what I wanted. With a simple command, godot-genesis export-project "Sanity Wars Reimagined" "Name Of Export Template", Genesis would handle grabbing a Godot executable and running a shell command to make Godot export the project using the provided export template, and then create a ZIP archive of the resulting export. The name of the export was the project name, followed by a build number using the semantics I chose (major.minor.patch.build). By providing a -b flag, I could also specify what kind of build this was (and thus which build number to increment). It works really well, and now that exports are so easy to do I am more willing to make them frequently, which allows me to quickly make sure my development changes work in the release builds.

Other Features and Improvements

There are many other features that were created for Sanity Wars Reimagined; to save time, I’ll simply give brief summaries of these. Some of these were not generalized enough to be ported back into the Genesis boilerplate, but the experience gained from creating them remains valuable nonetheless.

Generators

These nodes handle spawning entities, and I made the system flexible enough that I can pretty much generate any kind of object I want (though, in this case, I only used it to spawn Eyeballs and Tomes).

RectZone

This is a node which let me specify a rectangular area that other nodes (like Generators) could use to make spatial calculations against (aka figure out where to spawn things).

PixelPerfectCamera

This is a Camera node that was customized to support smoothing behavior rounded to pixel-perfect values. This helps reduce the amount of visual jitter that results from when a camera is positioned between whole integer values.

The reason this happens is because pixels can’t be rendered at fractional, non-integer values, so when a pixel art game asset is placed such that the underlying pixels don’t line up to a whole integer, the game engine’s renderer “guesses” what the actual pixel color values should be. This is barely noticeable for high-resolution assets because they consist of a huge number of pixels, but for something as low-resolution as pixel art, this results in visual artifacts that look terrible.

UI Theming

I finally took a dive into trying to understand how Godot’s theme system works, and as a result I was able to create themes for my UI that made it much simpler to create new UI elements that already worked with the visual design of the interface. I plan to build on my experience with UI themes for future projects, and ultimately want to make a base theme for the Genesis boilerplate, so I don’t have to create new themes from scratch.

State Machine Movement

I converted my previous Player character movement code to be based on a state machine instead of part of the node’s script, and this resulted in movement logic that was far simpler to control and modify.

As you can see, there were a lot of features I developed for Sanity Wars Reimagined, independent of gameplay aspects. A large part of what I created was generalized and reusable, so I can put the code in future projects without having to make modifications to remove Sanity Wars-specific functionality.

Complications

No human endeavor is perfect, and that is certainly true for Sanity Wars Reimagined. In fact, I made a lot of mistakes on this project. Fortunately, all of these mistakes are things I can learn from to make future projects better. I’ll highlight some of these issues and mistakes now.

Both Rebecca and I learned a lot from the mistakes we made developing this project, but I’m specifically focusing on my mistakes in this article.

New Systems Introduced New Complexities

The big systems I added, like Resolution Management and Screen Management, added lots of functionality to the game. With that, however, came gameplay issues that arose as the result of the requirements integrating with these systems introduced.

Take ScreenManager, for example. The system included the ability to have screens running visual updates during the transition, so the screen’s render texture didn’t look like it was frozen while fading from one screen to the next. By creating this capability, however, I needed to modify the existing game logic to take into account the idea that it could be running as part of a screen transition; for instance, the player character needed to be visible on the screen during the transition, but with input disabled so the player couldn’t move while the transition was running.

Another issue the ScreenManager refactor created had to do with resetting the game when the player chose to restart. Before, screens were loaded from file when being switched to, and being unloaded when switched from, so restart logic was as simple as using node _ready() methods to set up the game logic. After the refactor, this was no longer true; to avoid the loading penalty (and subsequent screen freeze) of dealing with loading scenes from file, ScreenManager instead kept inactive screens around in memory, adding them to the scene tree when being transitioned to and removing them from the scene tree when being transitioned from. Since _ready() only runs once, the first time a node enters the scene tree, it was no longer usable as a way to reset game logic. I had to fix this by explicitly creating reset functions that could be called in response to a reset signal emitted by the controlling screen, and throughout the remaining development I encountered bugs stemming from this change in game reset logic.

ResolutionManager, while allowing for crisp-looking UI, created its own problems as well. While the UI could be scaled down as much as I wanted, at smaller resolutions elements would render slightly differently from how they looked at 1920×1080. The reason for this was, ironically, similar to the issues with scaling pixel art: by scaling the UI down, any UI element whose size dimensions did not result in whole-number integers would force Godot’s renderer to have to guess what to render for a particular pixel location on the monitor. Subsequently, some of the UI looked bad at smaller resolutions (such as the outlines around the spell selection indicators). I suspect I could have addressed this issue by tweaking the UI design sizes to scale cleanly, but my attempts to change those values resulted in breaking the UI in ways I couldn’t figure out how to fix (largely due to my continued troubles understanding how to create good UI in Godot). In the end, I decided that, with my limited amount of time, trying to fix all the UI issues was less important than fixing the other issues I was working on, and ultimately the task was cut during the finishing stages of development.

I’m guessing most people won’t notice, anyway, since most people likely have the game at fullscreen, anyway.

Complexities arising from implementing new systems happened in other ways throughout the project as well, although the ones stemming from ScreenManager and ResolutionManager caused some of the bigger headaches. Fixing said issues contributed to extending development time.

Designing for Randomization

One of the core mechanics of Sanity Wars (original and Reimagined) is that all the entities in the game spawn at random locations on an unchanging set of maps. At the time I created the mechanic, my thought was that this was a way to achieve some amount of replayability, by having each run create different placements for the tomes, eyeballs, portals, and player.

Playtesters, however, pointed out that the fully random nature of where things spawned resulted in wide swings of gameplay experience. Sometimes, you got spawns that made runs trivially easy to complete; other times, the spawns made runs much more difficult. This had a negative impact on gameplay experience.

The way to solve this is through creating the means of controlling just how random the processes are. For example, I could add specific locations where portals were allowed to spawn, or add logic to ensure tomes didn’t spawn too close to portals. Adding controlled randomness isn’t easy, however, because by definition it means having to add special conditions to the spawning logic beyond simply picking a location within the map.

The biggest impact of controlled randomness wasn’t directly felt with Sanity Wars Reimagined, however; it was felt in our plans to expand directly off of this project for our next game. Given that random generation was a core element of gameplay, that meant adding additional elements would also need to employ controlled randomness, and that would likely result in a lot of work. On top of that, designing maps with randomness in mind is hard. It would likely take months just to prototype ideas, let alone flesh them out into complete mechanics.

This aspect, more than anything else, was a huge influence in our decision to not expand on Sanity Wars Reimagined for the next project, but to concentrate on a more linear experience. (More on that later.)

Clean Code

If you’re a programmer, you might be surprised at seeing “clean code” as a heading under complications. If you’re not a programmer, let me explain, very roughly, what clean code is: a mindset for writing code in such a way that it is easy to understand, has specific responsibilities, and avoids creating the same lines of code in different files; through these principles one’s code should be easier to comprehend and use throughout your codebase.

Under most circumstances, writing clean code is essential for making code not only easier to work with, but faster to develop. So how did writing clean code make Sanity Wars Reimagined more complex?

Simply put, the issue wasn’t strictly with adhering to clean code principles in and of themselves; the issue was when I spent a lot of time and effort coming up with clean code for flawed systems. Clean code doesn’t mean the things you create with it are perfect. In fact, in Sanity Wars Reimagined, some of the things I created wound up being harmful to the resulting gameplay.

A prime example of how this impacted development is the way I implemented movement for the Eyeball entity. I had the thought of creating a steering behavior-based movement system; rather than giving the entity a point to navigate to and allowing it to move straight there, I wanted to have the entity behave more like real things might move (to put it in very simple terms). I then spent a long time creating a locomotion system that used steering behaviors, trying to make it as clean as possible.

In the end, my efforts to integrate steering behavior movement were successful. There was a huge flaw, however; the movement hampered gameplay. Steering behaviors, by design, are intended to give less-predictable behavior to the human eye, which makes it harder to predict how the eyeball is going to move when it isn’t going in a straight line. This style of movement also meant the Eyeballs could easily get in a position where it was difficult for the player to hit them with the straight-line spirit bullet projectile, which was specifically intended for destroying Eyeballs. Since steering behaviors work by applying forces, rather than explicitly providing movement direction, there wasn’t an easy, feasible way for me to tweak the movement to make it easier for the player to engage with Eyeballs.

In addition to making Eyeballs less fun to play against, the steering behaviors also made it hard to make Eyeballs move in very specific ways. When I was trying to create a dive attack for the Eyeball, I literally had to hack in movement behavior that circumvented the steering behaviors to try and get the attack to visually look the way I wanted to; even then, I still had a lot of trouble getting the movement to look how I felt it should.

How did clean code contribute to this, precisely? Well, I’d spent a lot of time creating the locomotor system and making it as clean an implementation as I possibly could, before throwing it into the gameplay arena to be tested out and refined. If there had been time to do so, I likely would have needed to go back and refactor the Eyeball movement to not use steering behaviors; all that work I’d spent making the steering behavior implementation nice and clean would’ve gone to waste.

Don’t get me wrong; writing clean code is very important, and there is definitely a place for it in game development. The time for that, however, is not while figuring out if the gameplay works; there’s no sense in making something clean if you’re going to end up throwing it out shortly thereafter.

Playtesting

I didn’t let other people playtest the game until way too late in development. Not only did that result in not detecting crashes in release builds, it also meant I ran out of time to properly take feedback from the playtests and incorporate it back into the game.

For the first three months of development, I never created a single release build of Sanity Wars Reimagined. I kept plugging away in development builds. The first time I attempted exporting the project was the day, no, the evening I was scheduled to bring the game to a live-streamed playtest session with IGDA Twin Cities. As a result, it wasn’t until two hours before showtime that I found out that my release builds crashed on load. I spent a frantic hour hack-fixing the things causing the crashes, but even with that, the release build still had a major, game-breaking bug in it: the testers couldn’t complete the game because no portals spawned. Without being able to complete the game, the testers couldn’t give me good feedback on how the game felt to them. From that point onward, I made a point of testing exports regularly so that something like that wouldn’t catch me off-guard again.

The next time I brought the game out for playtesting was in the middle of January 2022, three months after the first playtest. At that point, I’d resigned myself to the fact that Sanity Wars Reimagined didn’t feel fun, and was likely going to be released that way; my intent with attending the playtest was to have people play the game and help me make sure I didn’t have any showstopping bugs I’d need to fix before release. What I wasn’t expecting (and, in retrospect, that was silly of me) was that people had a lot to say about the game design and ways it could be made more fun.

To be honest, I think I’d been stuck so long on the idea that I wanted to faithfully recreate the original game’s mechanics that I didn’t even think about making changes to them. After hearing the feedback, however, I decided that it would be more important to make the game as fun as I could before release, rather than sticking to the original mechanics.

That playtest, however, was one and a half weeks before the planned release date, meaning that I had very little time to attempt making changes of any significance. I did what I could, however. Some of the things I changed included:

- Removing the sacrifice aspect of using spells. Players could now access spells right away, without having to sacrifice their maximum sanity.

- Giving both the spells dedicated hotkeys, to make them easier (and thus more likely) to be used.

- Adding a countdown timer, in the form of reducing the player’s maximum sanity every so often, until the amount was reduced to zero, killing the player. This gave players a sense of urgency that they needed to resolve, which was more interesting than simply exploring the maps with no time constraints.

- Changing the Eyeball’s attack to something that clearly telegraphed it was attacking the player, which also made them more fun to interact with.

- Adding a scoring system, to give the player something more interesting to do than simply collecting tomes and finding the exit portal.

- Various small elements to add juice to the game and make it feel more fun.

Although we did wind up extending the release date by a week (because of dealing with being sick on the intended release week), I was surprised with just how much positive change I was able to introduce in essentially two and a half weeks’ worth of time. I had to sacrifice a lot of clean code principles to do it (feeding into my observation about how doing clean code too early was a problem), but the end result was an experience that was far more fun than it was prior to that play test.

I can only imagine how much more fun the game could’ve been if I’d had people involved with playtesting in the early stages of development, when it would’ve been easier to change core mechanics in response to suggestions.

Thanks to the IGDA Twin Cities playtest group, and specifically Mark LaCroix, Dale LaCroix, and Lane Davis, for offering many of the suggested changes that made it into the final game. Thanks also to Mark, Lane, Patrick Grout, and Peter Shimeall for offering their time to playtest these changes prior to the game’s release.

Lack of a Schedule

I mentioned previously that I’d thought the entire Sanity Wars Reimagined project wouldn’t take more than a month, but I hadn’t actually established a firm deadline for when the project needed to be done. I tried to implement an approach where we’d work on the project “until it felt ready”. I knew deadlines were a way that crunch could be introduced, and I wanted to avoid putting ourselves in a situation where we felt we needed to crunch to make a deadline.

The downside, however, was that there wasn’t any target to shoot for. Frequently, while working on mind-numbing, boring sections of code, I had the dread fear that we could wind up spending many more months on this project before it would be finished. This fear grew significantly the longer I spent working on the project, my initial month-long estimate flying by the wayside like mile markers on a highway.

Finally, out of exasperation, I made the decision to set a release date. Originally, the target was the middle of December 2021, but the game wasn’t anywhere near bug-free enough by that point, so we pivoted to the end of January 2022, instead. As that deadline approached, there were still dozens upon dozens of tasks that had yet to be started. Instead of pushing the deadline out again, however, I went through the list to determine what was truly essential for the game’s release, cancelling every task that failed to meet that criteria.

Things that hit the cutting room floor include:

- Adding a second enemy to the game, which would’ve been some form of ground unit.

- Refactoring the player’s jump to feel better.

- Fixing a bug that caused the jump sound to sometimes not play when it should.

- Adding keyboard navigation to menus (meaning you had to use the mouse to click on buttons and such).

- Create maps specifically for the release (the ones in the final build are the same as the ones made for the second playtest).

It’s not that these things wouldn’t have improved the game experience; it’s just that they weren’t essential to the game experience, or at least not enough to make it worth extending the release date to incorporate them. By this point, my goal was to finish the game and move on to the next project, where, hopefully, I could do a better job and learn from my mistakes.

These are far from the only complexities that we had to deal with during Sanity Wars Reimagined, but they should serve to prove that a lot of issues were encountered, and a lot of mistakes were made. All of these things, however, are learning opportunities, and we’re excited to improve on the next project.

Improvements for Next Time

There’s a lot of things that I want to try for the next project; many of them serve as attempts to address issues that arose during the development of Sanity Wars Reimagined.

Have A Planned Release Date

I don’t want to feel like there’s no end in sight to the next project, so I fully intend to set a release date target. Will we hit that target? Probably not; I’m not a great estimator, and life tends to throw plenty of curveballs that wreak havoc on plans. By setting an end goal, however, I expect that it will force us to more carefully plan what features we want to try and make for the next game.

In tandem with that, I want to try and establish something closer to a traditional game development pipeline (or, at least, what I understand of one), with multiple clearly-defined phases: prototyping, MVP, alpha, beta, and release. This will hopefully result in lots of experimentation up front that settles into a set of core mechanics, upon which we build lots of content that is rigorously tested prior to release.

Prototype Quickly Instead of Cleanly

Admittedly, the idea of not focusing on making my code clean rankles me a bit, as a developer, but it’s clear that development moves faster when I spend less time being picky about how my code is written. Plus, if I’m going to write something, find out it doesn’t work, and throw it away, I want to figure that out as quickly as possible so I can move on to trying the next idea.

Thus, during the prototyping phase of the next project, I’ll try to not put an emphasis on making the code clean. I won’t try to write messy code, of course, but I’m not going to spend hours figuring out the most ideal way to structure something. That can wait until the core mechanics have been settled on, having been playtested to confirm that said mechanics are fun.

Playtest Sooner Rather Than Later

The feedback I received from the final big playtesting session of Sanity Wars Reimagined was crucial in determining how to make the game more fun before release. For the next project, I don’t want to wait that long to find out what’s working, what’s not, and what I could add to make things even more fun.

I don’t think I’ll take it to public playtesting right away, but I’ll for sure reach out to friends and interested parties and ask them to try out prototype and MVP builds. It should hopefully be much easier to make suggested changes during those early stages, versus the week before release. With more frequent feedback, I can also iterate on things more often, and get the mechanics to be fun before locking them down and creating content for them.

Make a Linear Experience

After realizing how much work it would be to try and craft a good random experience, I’ve decided that I’m going to purposely make the next game a linear experience. In other words, each playthrough of the game won’t have randomness factoring into the gameplay experience. This may be a little more “boring”, but I think doing it this way will make it easier for me to not only practice making good game design, but make good code and good content for as well.

Will it be significantly less fun than something that introduces random elements to the design? Maybe, maybe not. We’ll find out after I attempt it!

Those are just a few of the things I intend to try on the next project. I don’t know if all of the ideas will prove useful in the long run, but they at least make sense to me in the moment. That’s good enough, for now. Whatever we get wrong, we can always iterate on!

Conclusion

That’s the story of Sanity Wars Reimagined. We started the project as an attempt to make a quick release to gain experience creating games, and despite taking significantly longer than planned, and the numerous mistakes made along the way, we still wound up releasing the game. Along the way, we developed numerous technologies, and learned lots of lessons, that should prove immensely useful for our next project. Because of that, despite the resulting game not being as fun as I wish it could’ve been, I consider Sanity Wars Reimagined a success.

What’s next for Rebecca and I? It’ll for sure be another platformer, as that will allow us to make good use of the technologies and processes we’ve already developed for making such games. I fully expect there will be new challenges and complications to tackle over the course of this next project, and I can’t wait to create solutions for them, and learn from whatever mistakes we make!